Lily Kostrzewa (Lih-ting Li)

Preface: This January, I attended a wonderful lecture at the State University of New York Maritime College, and I’d like to share it with everyone. (中文版)

Attorney Ray Dowd delivered an in-depth presentation on the ongoing global struggle to recover artworks stolen during the Nazi era, highlighting both historical context and current legal battles. His talk emphasized that, despite decades of litigation and international agreements, significant gaps remain in the restitution of looted cultural property.

1. Historical Background and Legal Framework

Dowd reviewed the legal foundations governing wartime art theft, beginning with the 1907 Hague Convention IV, Article 56, which requires that cultural property seized or destroyed during conflict be subject to legal proceedings. After World War II, the United States and other Allied nations established mechanisms to identify and return stolen artworks. However, many pieces remained unclaimed or were absorbed into museum collections across Europe and the United States.

From 1933 to 1945, Jewish families were systematically stripped of property through discriminatory policies, including boycotts, punitive taxes, forced sales, and asset liquidation by European banks. These actions constituted property crimes, yet Cold War priorities led the U.S. government to deprioritize restitution efforts after 1945.

2. Major Restitution Cases Discussed

- Cassirer–Thyssen Case

Dowd highlighted the long-running Cassirer-Thyssen case, which has reached the U.S. Supreme Court twice and passed through the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. The dispute centers on a painting acquired by Spain’s national museum during World War II. Although Spain claimed neutrality during the war, it maintained close alignment with Germany and accepted artworks with clear ownership markings. Spain continues to resist returning the painting despite evidence of Nazi-era theft.

(After remand, the Ninth Circuit reaffirmed that Spanish law applies under California’s choice-of-law rules. Under Spanish law, a good-faith possessor can acquire title through prescription.

In January 2024, the Ninth Circuit again ruled that the Thyssen-Bornemisza Foundation is the lawful owner. In August 2024, the court officially closed the case, ending the Cassirer family’s legal avenues in the U.S. Why the Case Matters

Legal Significance-

Clarifies how U.S. courts apply choice-of-law rules in FSIA cases. Highlights the tension between national cultural institutions and heirs of Nazi-looted art. Shows how differing national property laws (e.g., Spain’s acquisitive prescription) can determine outcomes.

Historical & Ethical Significance-

Raises enduring questions about restitution, moral responsibility, and the legacy of Nazi-era theft. Demonstrates the challenges heirs face even when provenance is undisputed.)

- Egon Schiele’s “Russian Prisoner” Case

Dowd also discussed his current litigation involving the Art Institute of Chicago and the heirs of a “Russian Prisoner” sketched by Egon Schiele during his time in an Austrian war prison. The family seeks the return of the artwork, which is currently held by the museum.

(The legal case surrounding Egon Schiele’s Russian Prisoner of War (1916) centers on a restitution claim by the heirs of Fritz Grünbaum, a Jewish cabaret performer murdered by the Nazis. The Art Institute of Chicago retained possession, with a 2023 ruling initially favoring the museum, but the case highlights ongoing Nazi-looted art disputes.

Key Details of the Russian Prisoner Case-

The Artwork: A 1916 drawing by Egon Schiele, often known as Russian Prisoner of War or Portrait of a Russian Prisoner. The Claim: Heirs of Fritz Grünbaum argue the drawing was stolen by Nazis after he was sent to Dachau concentration camp. The Dispute: The Art Institute of Chicago, which has owned the drawing since 1966, argued in court that the work was not stolen, leading to a 2023 dismissal of the heirs’ claims. Significance: This case is part of a broader, high-profile legal battle regarding the restitution of the entire Grünbaum collection.)

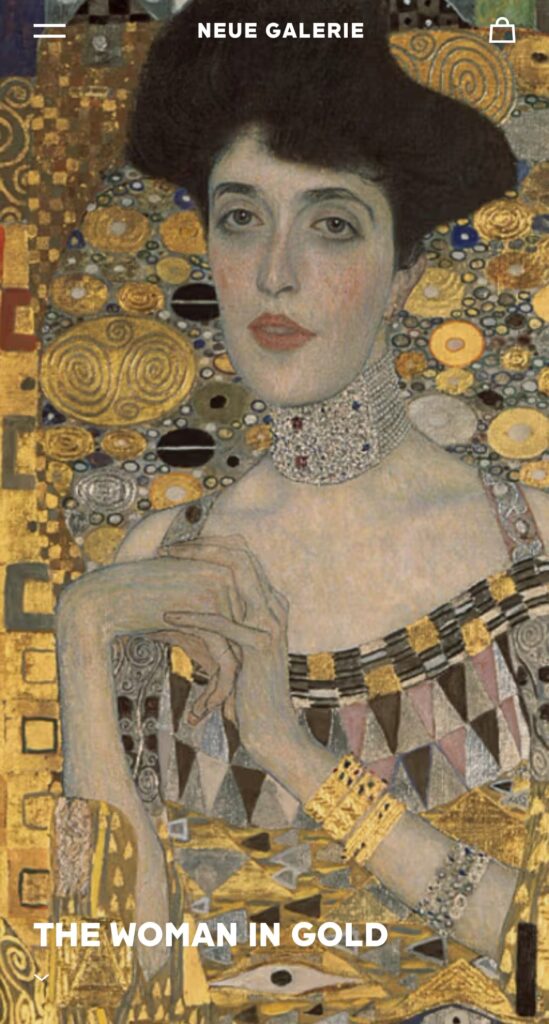

- Gustav Klimt’s “Woman in Gold” Case

Gustav Klimt’s Woman in Gold—originally Portrait of Adele Bloch‑Bauer I—was stolen from the Jewish Bloch‑Bauer family by the Nazis in the early 1940s and kept by Austria for decades. The painting was kept in the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere in Vienna, Austria for decades after it was seized by the Nazis.

Maria Altmann, Adele’s niece, fought a long legal battle that reached the U.S. Supreme Court and ultimately won the painting back in 2006.

After Maria Altmann won the restitution case in 2006, Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch‑Bauer I (“Woman in Gold”) was sold to Ronald S. Lauder, the heir to the Estée Lauder cosmetics empire.

He purchased the painting for $135 million, which at the time was the highest price ever paid for a painting.

Lauder acquired the work specifically to become the centerpiece of the Neue Galerie New York, the museum he founded and opened in 2001 to showcase German and Austrian art.

Today, Woman in Gold remains the museum’s most iconic and celebrated masterpiece.

3. Persistent Challenges in Restitution

Despite international law, many Nazi-looted artworks remain in private hands or museum collections. Research from the Art Institute of Chicago indicates that approximately 20% of such works continue to circulate in private markets, eventually entering U.S. museums. Between 1945 and 1962, U.S. servicemen alone recovered nearly 4,000 stolen artworks.

Museums and collectors have historically resisted restitution claims, often arguing that families waited too long to act or that entire family lines were destroyed, making claims impossible. Many heirs were unaware that the artworks existed or had been stolen.

4. Legislative Developments

To address these barriers, the U.S. Congress passed legislation in 2016 extending the statute of limitations to six years from the date an heir discovers the artwork. This period was further extended in 2023. Congress has also explored limiting foreign sovereign immunity to allow lawsuits against foreign governments; however, Germany and France have declined to participate.

In 2022, New York State enacted a law requiring museums to label artworks with Nazi-era provenance, increasing transparency for the public. On March 5, 2024, thirty-four countries jointly committed to strengthening efforts to return Nazi-looted art to rightful heirs.

5. International Complications

Dowd noted that Russia holds more Nazi-looted art than any other country, largely due to agreements made between President Roosevelt and Stalin near the end of World War II. Many artworks taken by the Nazis were transferred to Russia and remain inaccessible.

6. Steps Toward Resolution

Dowd outlined three essential steps for meaningful restitution:

- Public awareness to ensure families know what exists and where.

- Museum-led provenance research to identify stolen works.

- Independent research groups that assist heirs are often compensated through a share of recovered value.

7. Audience Questions and Key Insights

- Who advocates for restitution besides Jewish families?

Primarily Holocaust survivors and their descendants, as they remain the most directly affected. - How is inheritance determined if heirs have died?

Probate courts handle succession and determine rightful heirs. - Why invest in such lawsuits?

Many heirs are donors or board members of museums. When stolen artworks surface, it creates reputational and tax-related complications, especially when past donations involved questionable provenance.

8. Cultural and Ethical Context

Dowd concluded by emphasizing that Nazi property crimes were part of a broader effort to erase Jewish cultural influence. Hitler targeted Jewish art collections to eliminate their presence in European cultural life, while labeling modernist works as “degenerate art.” These crimes were often concealed, making recovery efforts today even more complex.

<2026-02-02>